Building a sustainable future: How recycled aggregates are transforming construction and demolition waste

Partner Content produced by KHL Content Studio

27 June 2024

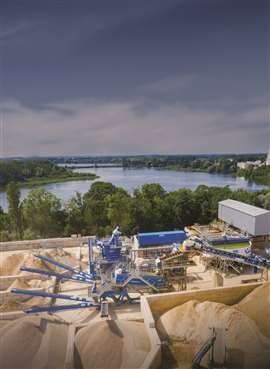

The construction and demolition waste sector – along with excavated soils recycling – is a market on the rise, with an estimated compound annual growth rate of 5.6% from this year until 2030.

As wet processing technology advances, million more tonnes of recycled material can potentially be utilised by the construction industry

As wet processing technology advances, million more tonnes of recycled material can potentially be utilised by the construction industry

In global terms, Europe accounts for just shy of 30% of the global waste management market and for several reasons, even more impressive growth in this sector could be on the cards.

The increasing demand for construction materials closer to urban areas is one of those reasons for this, along with a realisation that natural resources are depleting, so a conscious effort is needed to use them wisely.

Innovation is aiding growth in the sector, with advances in technology allowing for more complex waste streams to be processed and the standard of washed product to be on par with natural materials.

A challenging process

Recycling so-called waste materials is not an easy process, especially when the material consists of such variable properties.

Eunan Kelly, head of business development for Europe at the wet processing solutions provider CDE, says, “An operator can receive materials from anywhere within a radius of 50 or 60 miles [80 or 100 km], where the geology can change considerably. You never know from day to day, or load to load, what is coming in.”

With this in mind, businesses operating in the recycling sector must develop processes that can adapt to these ever-changing geologies, while consistently delivering in-spec construction products off the belt.

Kelly says, “The major considerations are sticky clays adhering to aggregates, the lightweights contained with the feedstock [woods, plastics etc], and high levels of fines [0.063mm] within the materials and the variations of these levels, all needing to be removed.

Feed material from construction and demolition waste

Feed material from construction and demolition waste

“Surplus volumes within the sand grade could render the sand unusable for construction applications. Proportions of the mid sand range needs to be removed to bring the final sand product into specification for use [EN12620 in Europe, for example].”

Water treatment and management is another major consideration as, very often, processing plants are located on sites that have no direct access to water, limited space for water lagoons or simply no authorisation to use them.

This is more than a little problematic, as these processes require a significant amount of water. To overcome this challenge, it is essential that as much of the process water as possible is managed and recovered for reuse in the washing process.

Looking at how the recycling market has progressed over the last decade, Kelly says CDE has been involved in washing almost 150 million tonnes of recycled material for reuse in the construction industry, and this ‘level of proof’ has provided confidence in the industry.

“The more we do it, the more acceptance it will gain,” he says. “We are moving in the right direction, with innovation, new technologies and a change in attitude, but we have a long way to go yet.

“More washed products are getting certification for concrete and structural uses. This provides the platform for others to enter the space with confidence.”

Wet processing technology is the key for businesses to turn mineral waste into in-spec certified high-value sand and aggregates

Wet processing technology is the key for businesses to turn mineral waste into in-spec certified high-value sand and aggregates

Legislating for success

Looking at the materials that can currently be processed, there is undoubted growth in the reuse of demolition debris, excavation soils from site clearance, and materials from utility works and foundation preparations.

According to Kelly, “More and more contaminated soils are coming to our customers’ facilities – PFAS/PFOS [polyfluoroalkyl substances / Perfluorooctane sulfonic acid], heavy metals, and hydrocarbons, among others.”

When it comes to aggregates used in construction, the majority still comes from extraction, but the use of secondary aggregates is on the rise, thanks to washing technologies, which can produce recycled materials similar to, if not better than, natural materials, depending on the application.

Kelly says the sort of aggregates being processed in his experience are customer driven and regionally driven. “If we take, for example, Oslo and Sweden,” he says, “the main sources of excavated material will be demolition sites where new construction will take place.

“After the demolition has taken place – the selective demolition has happened, the big fall is done and all that rubble is crushed – the concrete is crushed and cleared off site. Most of these materials along with foundation digs can be processed and made valuable again.”

Where these recycled materials could be used, and where they are able to be used, are however two different things.

In terms of size classification and cleanliness for use, the washed material could meet all current specifications. In some cases, when comparing a recycled product sieve analysis and a natural product sieve analysis, it is generally impossible to identify which is which.

An application-based approach

Kelly believes the attitude and legislation needs to catch up with the current technology and innovation.

“We need an application-based approach,” he says, “if the reuse of recycled materials is to have the desired effect of sustaining natural resources.

Wet processing technology is keeping millions of tonnes of material each year away from landfill

Wet processing technology is keeping millions of tonnes of material each year away from landfill

“We should avoid using natural materials in applications where a recycled substitute can provide the same result.”

We are seeing an increasing number of materials businesses successfully producing CE- and BSI-certified concrete products from recycled materials, including competitive concrete for non-structural – but still high value – construction projects, with some applications achieving beyond C45 spec.

Whether recycled materials can be used in structural construction – in bridges and buildings, for example – is still a moot point.

“We don’t need to replace every single grain of natural material,” says Kelly. “But there are numerous applications where recycled material fulfils all the requirements of a construction application. Why on earth would we use a top-class granite and riverbed sand for an application to fix a sign into the ground?

“A high percentage [75%] of concrete is non-structural, and 50% is C25 and below. There’s still the opportunity to be impactful on much of the concrete market without compromising the big builds. It will never replace all the demand.

Kelly stresses that, within new project utilities, it should be mandatory to use recovered materials. This would include applications such as pipe and cable ducting and paving brick base layer sands.

A social conscience

Advances in processing technology are allowing for increasingly challenging waste streams to be processed

Advances in processing technology are allowing for increasingly challenging waste streams to be processed

He reflects that both the profile and the perceptions of his company’s customers are changing.

“Our primary customers are the suppliers to the construction industry,” he says. “These are hugely business savvy people who – to refer to Marga Hoek’sThe Trillion Dollar Shift – have spotted the opportunity to not only do business for good, but also do good business.

“More recently, the customer profile is broadening as more of the larger companies recognise the opportunity in this space.”

There are numerous examples of how businesses have benefitted from making the leap into materials recycling, the main advantage being better control of their supply chain.

Other potential advantages include a reduction in operational and transport costs, the creation of new revenue streams and the competitive edge offered by utilising sustainable materials.

Another driver is the social conscience around sustainability. The knowledge that natural resources are depleting has created a “conscious notion that we need to do something”, Kelly says, and “that notion is accelerating the growth of recycling.”

He also admits that “there are a number of barriers that we have to continue to overcome, but we will keep knocking them down.”

The challenge of going green

The standard of washed product is on par with natural materials and they are getting certification for concrete and structural use

The standard of washed product is on par with natural materials and they are getting certification for concrete and structural use

When considering the regulations surrounding sustainability in the construction sector, it would be logical to assume they would be focused on accelerating ‘green’ practices, as opposed to holding them back.

Yet there appears to be little in the way of government funding or grants for businesses looking to preserve natural resources.

Kelly says, “Investing in equipment to recycle material is a socially and environmentally beneficial practice. Businesses in this sector are usually supplying materials to the construction industry and always trying to find somewhere to dispose of the waste.

“Alternatively, they are handling waste, usually as an inert landfill, and trying to source virgin materials for use in the construction industry.

“Maybe the lack of funding stems from the strength of the return investment, but generally businesses need the kick start to get to that point.”

Furthermore, with companies reaching capacity at their landfills, Kelly explains that an investment in plant could replace the need for them to buy a new landfill site or extend their site.

“Given the difficulties with permitting and process, plant is an easier route to go,” he says.

Eunan Kelly, CDE’s head of business development in Europe

Eunan Kelly, CDE’s head of business development in Europe

Another is operators who already run natural quarries or sand pits, who see this solution as a way to offer an alternative that extends the life of their current reserve.

For businesses with even a passing interest in construction waste recycling, a more forward-thinking approach from funding bodies in Europe could prove beneficial.

The problem with sand

The situation with sand today is quite troubling; our appetite for sand consumption is increasing and, with the global population growing, it is expected that by 2050 almost 70% of the world’s population will live in urban areas.

That 70% equates to the total global population today, and this will put huge pressure on global sand aggregate reserves as construction tries to keep up with demand.

“We are dredging river sand at rates that far outstrip nature’s ability to replace it,” says Kelly. “Consequently, the global illegal sand trade represents more than illegal logging, gold mining and fishing combined.

“There is a varying story throughout Europe. London, for example, is at a huge sand deficit and is continuously transporting sand in from as far away as Devon and Cornwall.

Recycled sand stockpiles at Velde Pukk in Norway

Recycled sand stockpiles at Velde Pukk in Norway

“Typically, areas in the rest of Europe that have a higher availability of either aggregate, or sand, have a deficit of the other – at least a deficit close to where the material is required.”

Kelly adds, “I see a huge variation in the price of sand throughout Europe, due to its availability, levels of demand and the associated transportation of getting sand to where it’s needed.”

He reckons a major issue is that all concrete sand is considered the same. “If we took the application specification approach, then we could reduce the volume that needs to be transported over these huge distances.”

What is required is a conscious effort to not waste the resource when there is a viable alternative. And a conscious effort to deliver forward-thinking regulation that could open the door to new business opportunities… opportunities that, when we look at our ageing building and infrastructure stock, are visible all around us.

--------

All images courtesy CDE

--------

This article was produced by KHL’s Content Studio, in partnership with experts from CDE

|

About CDE With over 30 years of industry experience, wet processing solutions provider CDE Group, headquartered in Northern Ireland, has been solely focused on wet processing equipment, working across five regions within the natural processing and waste recycling sectors. The company is helping customers transform waste into valuable resources, diverting millions of tonnes of material from landfill and protecting sands in areas where natural reserves are in decline – laying the foundations for a circular economy. |

STAY CONNECTED

Receive the information you need when you need it through our world-leading magazines, newsletters and daily briefings.

CONNECT WITH THE TEAM